Lock-in starts to surpass security as main cloud concern

While the advantages of cloud are increasingly obvious, the main pitfalls often aren’t quite as well understood. It often appears from analyst reports and articles in the press that almost all workloads are now moving to the cloud.

Initially the main barrier to cloud adoption was security, but recent evidence indicates that public cloud is more and not less secure than legacy data centres. Recently Gartner called on chief information security officers CISOs to “dispel the [security] uncertainty surrounding cloud computing”.

Meanwhile, recent guidance from the Government Digital Service (GDS) also went someway to address buyers’ public cloud concerns around security, when it stated that well-executed use of public cloud services is appropriate for the vast majority of government information and services.

So with concerns around security addressed, what are the main remaining barriers to adoption?

I thought I’d seek the advice of some of the top cloud commentators. Here’s what I found.

Seek efficiencies of scale

Most experts now agree that private cloud simply isn’t economically viable, unless at scale. Unfortunately, very few private clouds achieve adequate scale. Even companies of the size of BP are turning their backs on private and hybrid cloud. BP found that private cloud looked, and smelled, too much like on-premises and it has chosen to go all in on public cloud.

Here are what some of the top pundits have to say on this issue:

- “Wake up! The private cloud fantasy is over.” David Linthicum, InfoWorld

- “Private cloud implementations generally are not working, and many companies that begin on a private cloud path end up going down a public cloud path.” UBS Managing Director Steven Milunovich

- “OpenStack and commercial private clouds can compete with and even beat public cloud on cost – but only at scale.” Owen Rogers, 451 Research

Avoid proprietary lock-in

It is all too easy to jump on the open standards band wagon for purely idealistic reasons, and the OpenStack movement has matured a great deal in recent years. It is certainly now ‘enterprise-ready’. I think one of the most measured articles on this topic was from Bernard Harzog in Network World:

While the major public cloud vendors (Amazon, Microsoft, Google) currently drive a great deal of innovation, they might also be trapping themselves and their customers into legacy situations.

Harzog (like many others others) focused on issues with workload portability between public clouds. As soon as you take advantage of any of their higher-level services, you lock yourself into the APIs associated with those services, and as soon as you write to any of their apps the same occurs.

It should be noted that data portability is going to be one of the key requirements of GDPR, a regulation which comes into effect May 2018. However, Harzog also goes on to focus on the tremendous burden that both AWS and Azure are taking on to have to out-innovate the entire hardware and software industry that they have chosen to compete with.

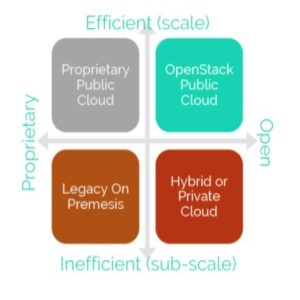

These first two issues might at first appear at odds with each other. Many would assume that seeking scale means going to AWS and Azure, or that avoiding lock-in means going to private cloud. In fact, there is a third way – the public cloud market is bigger than just AWS and Azure and there are firms operating at scale on OpenStack public clouds (see diagram).

Avoid currency fluctuations and sovereignty issues

Beyond these two main issues there are further issues around price (not only TCO but also fluctuations resulting from currency changes) and of course there is data sovereignty, all of which tends to favour local vendors that can again operate at scale. Here at diginomica/government, Derek du Preez summarised this well:

When you combine [price and currency fluctuations] with the data sovereignty concerns that coincide with a decision to leave the EU, I wouldn’t be surprised if more and more CIOs begin to consider UK cloud providers going forward.

Again it would be all too easy to jump on the sovereignty band wagon for purely domestic reasons, but this issue simply isn’t going to go away as long as Donald Trump is in the White House. US firms have been quick to dismiss recent privacy concerns and the implied threat to Privacy Shield as a ‘complete over-reaction’, in much the same way that they previously dismissed Max Schrems before he succeeded in making the EUCJ declare safe harbour invalid.

However, with the US Department of Justice appealing the Microsoft case, the Rule 41 amendments coming into force, Trump’s initial executive order with who knows how many more to come, and now the ruling against Google ordering it to hand over foreign emails, there will be fresh concerns in Brussels, and European privacy campaigners are going to be up in arms.

The last remaining foundation for Privacy Shield was the 1974 US Privacy Act (written well before email existed, in which time Europe has rewritten its privacy rules three times). Not only is this act out of date, but it is patchy and deficient at best. It now appears under assault.

Even if we could be confident that the new administration and US courts were committed to upholding European privacy rights, and could be certain that there would be no further orders or rulings like these, what we have seen so far suggests that the US is deeply divided, and with the current administration there can be no certainty.

UK clients, especially public sector bodies, with contracts with the US proprietary cloud firms need to make an immediate Privacy Impact Assessment, and if necessary, should seek expert legal advice. They may need to scope out migration options to move workloads so data privacy and sovereignty can be assured.

As they prepare for Brexit and GDPR as well as the Prime Minister’s new Industrial Strategy, which actively favours UK firms for government contracts and procurement for growth in the post-Brexit world, departments are going to need to weigh up the risks (in terms of data privacy and sovereignty and currency fluctuations) of doing business with non-UK providers.

This blog first appeared on Diginomica http://bit.ly/2lqC2RH.

Author: Bill Mew